Korea and "Death Valley"

After a short postwar respite in civilian life, Abbott reentered the U.S. Army

in 1947. In that capacity he led an Army Reserve unit and taught as an Assistant

Professor of Military Science at Syracuse University. The Army deployed Major

Abbott as an "Advisor" to the growing American military presence in South Korea

in September 1950, which in truth meant an active combat role. Abbott

effectively served as a field commander for the 7th Korean Division, which

ventured deep into enemy territory at the outset of the War. Abbott's fellow

American advisers dispatched with the unit consistently marveled at his bravery

in action. According to one report from the ground: "He [Abbott] was never

satisfied to be directing things -- he had to be out there on the front lines.

He was up there pushing all the time."

Abbott was captured in November 1950 when China entered the fray and unleashed a

massive offensive on U.S. and U.N. forces at the Yalu River on the border

between China and North Korea. The Communist armies overran their enemies,

picking up ground and prisoners alike in a counter-offensive that set the stage

for the rest of the conflict. Unfortunately, Abbott was among those trapped in

the sweep as U.S. and U.N. soldiers retreated behind the 38th Parallel and into

South Korea. As one close friend of Abbott's recalled: "Bob was captured because

he was out in the front lines pushing his troops to fight. He was caught out on

a limb and they [the Chinese Army] cut it off." Abbot subsequently spent nearly

three years (33 months) surviving cruel conditions and torturous treatment in a

communist POW camp referred to as "Death Valley" by many of its unfortunate

captives. He did not regain his freedom until September 1953 -- two months after

the July 1953 Armistice ended active combat -- during the last day of prisoner

exchanges in Operation Big Switch. Malnourished (his weight dropped from 200 to

100 pounds) and suffering from beriberi, pellagra, and dysentery, Abbott

underwent a period of convalescence and military-led acclimation for

repatriation. He finally returned to Rochester, and his anxious-but-overjoyed

family, later in the autumn of 1953. Once home, Abbott he received his final

promotion, to Lieutenant Colonel, and earned still further commendations:

another Bronze Star, a Distinguished Military Service Medal, and a Unit Citation

from the Republic of Korea.

On November 19, 1953, Col. Abbott gave a sworn affidavit testifying to the war

crimes he witnessed firsthand at "Death Valley." Abbott also provided some rough

mapping from memory to help the U.S. Army locate the POW camp. The following

comes from the statement Robert Abbott issued upon his release, describing his

capture and the conditions of his POW experience:

"My duty at the time of capture was Advisor to the Korean Army. I was a

Prisoner of War for 33 months... I was captured by the C.C.F., Chinese Communist

Forces, in the vicinity of Tokchon, North Korea. Prisoners were mistreated from

the start.

- No food or water

- Physical abuse applied

- Relief of personal items (clothing, dog tags, valuables, etc.)

- Constant interrogation

- Housing conditions were very crowded

- Very little food

- No medical attention

- Sick and wounded abandoned

[We marched] north to [a] mining camp, otherwise identified as 'Death

Valley,' [a] distance of approximately 100 miles. [It was a] forced march,

always at night... All those who were unable to keep up were left along the

roadside and it is assumed that they died. Shots were heard frequently behind us

on this march...

Approximately 1,000 men arrived at this camp on Christmas Day, 1950. Within

three months 300 men had died. Death resulted from lack of food, malnutrition,

exposure, lack of medical attention, poor sanitary conditions, poor housing,

lice, lack of fuel... This interrogation center was controlled by North Korean

Officers. They continuously applied physical abuse in their interrogations.

Starvation, lack of medical attention and forced labor also prevailed... In this

camp officers were exposed to a severe indoctrination program. These educational

periods lasted from early morning until late at night... Prisoners were exposed

to long periods of interrogation and failure to answer questions resulted in

prolonged periods of solitary confinement. The senior officers were continuously

being tried for crimes that they were not guilty of. These trials resulted in

long sentences of solitary confinement. Prisoners were denied mail from home,

news from the outside world. They were required to read only Communist

literature..."

Next: A Hero's Return

|

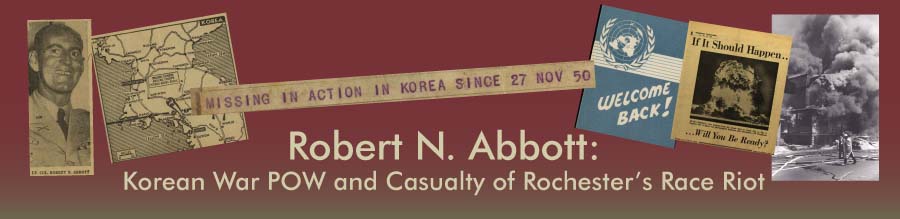

| In December 1950 all of Rochester learned that native son Robert Abbott had gone missing in action in North Korea. |

|

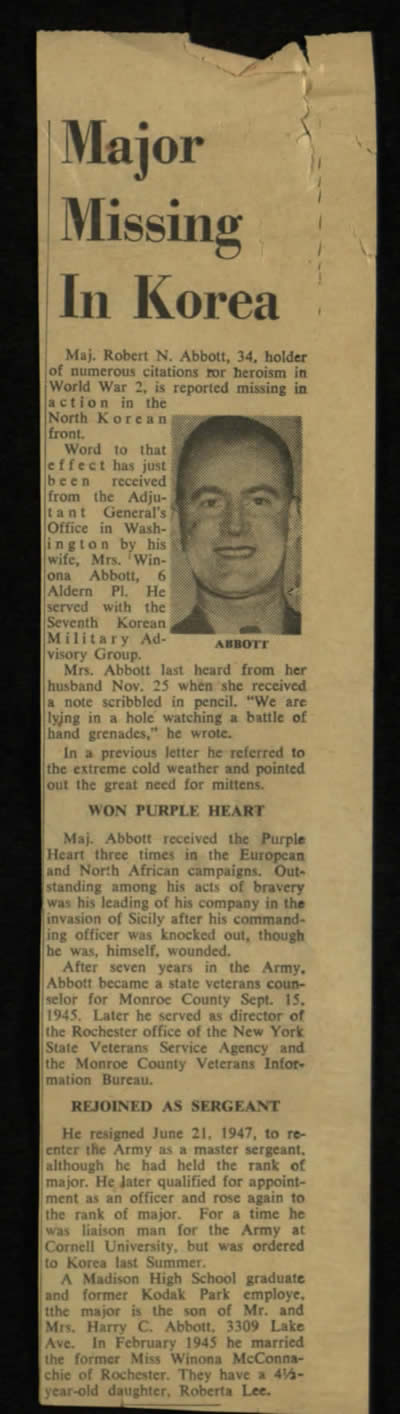

| This telegram from December 6, 1950 alerted Winonna Abbott that her husband was "missing in action in Korea." It was eventually determined that he had been taken prisoner. |

|

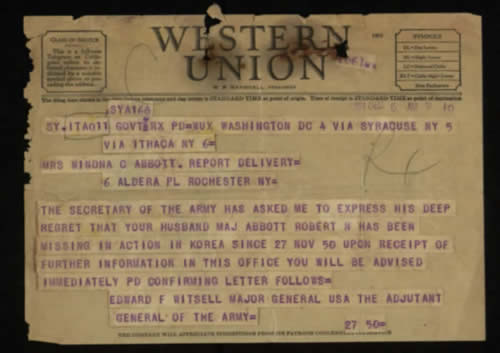

| The Democrat & Chronicle printed this map in late December 1950, explaining recent military setbacks in Korea following a Communist counter-offensive campaign that pushed U.S. and U.N, forces behind the 38th Parallel. Abbott was taken prisoner during this surge. Click to see detail. |

|

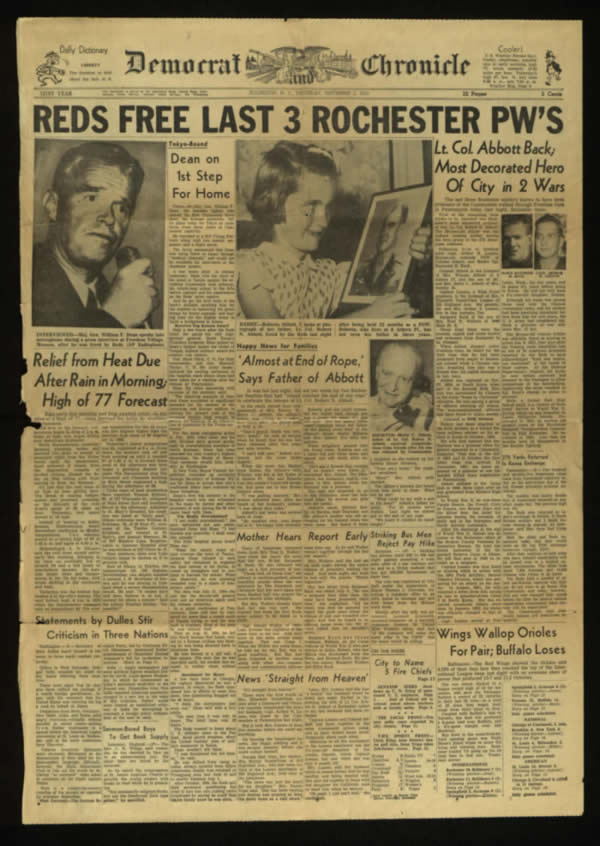

| Sweet relief in September 1953: Almost three years after his capture, Rochester learns that the release of Robert Abbott occurred during the final day of prisoner exchanges in Operation Big Switch. Click to see detail. |

|

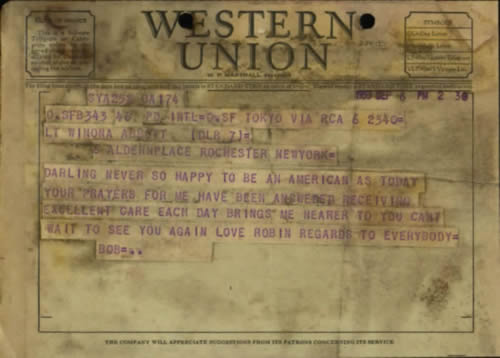

| Newly freed Colonel Abbott's first telegram to his wife Winonna. |

|

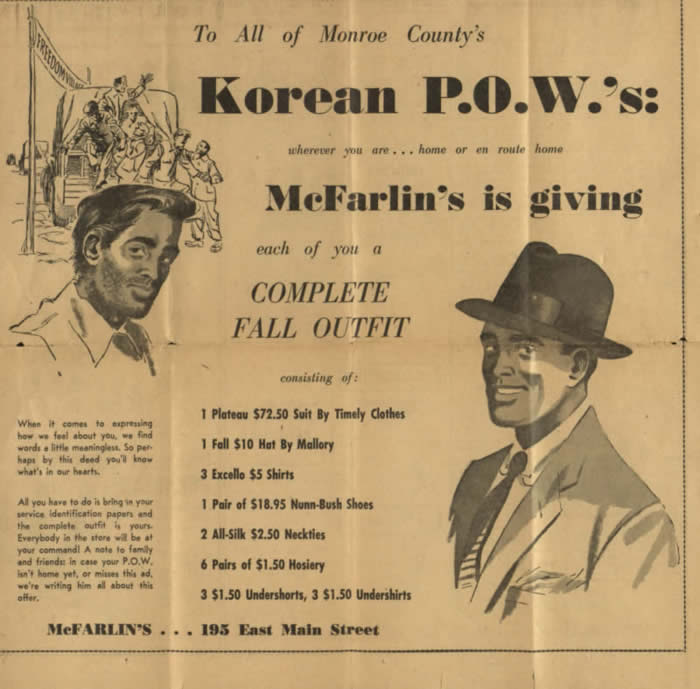

| A full-page newspaper promotion from McFarlin's Department Store promised a complete fall outfit to returning Korean POWs. |

|

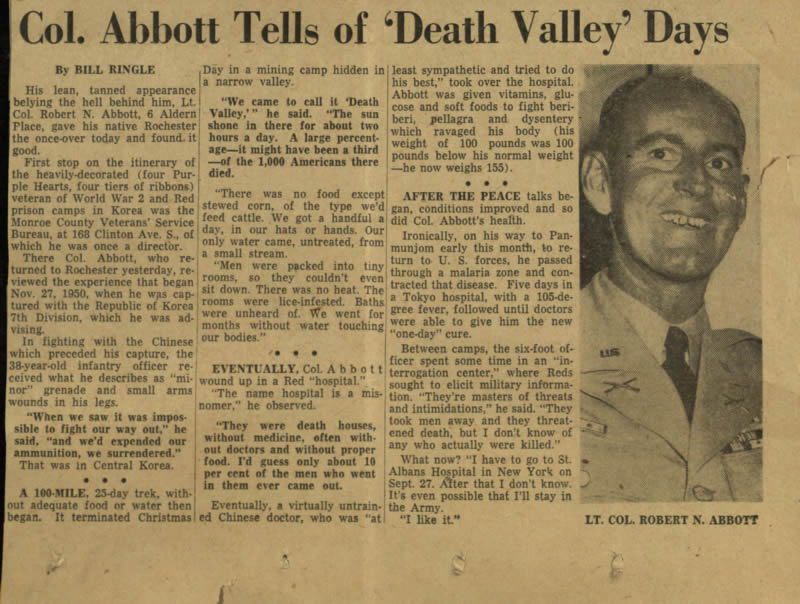

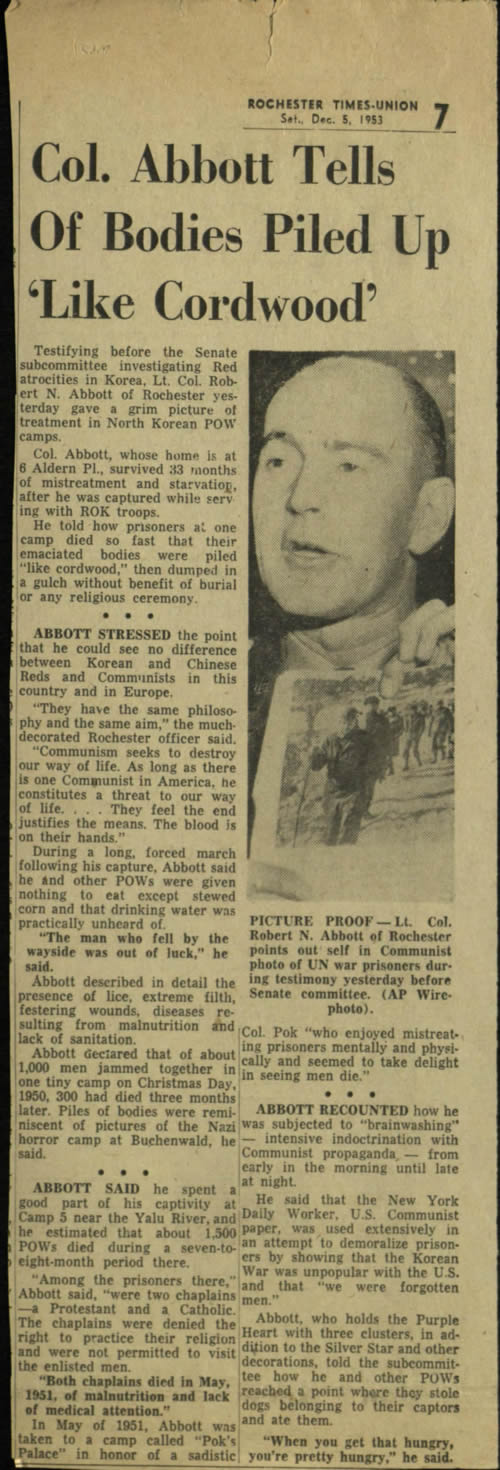

| A noticeably thin Colonel Abbott returned to Rochester, after giving testimony to the grim conditions of his experience in a Communist prison camp. |

|

| Reorientation materials given to returning POWs. Abbott was given this literature during his rehabilitation period. |

|

| Robert Abbott brought this pamphlet home with him from his convalescence. It can be visited in the Local History Division of the Rochester Public Library. |

|

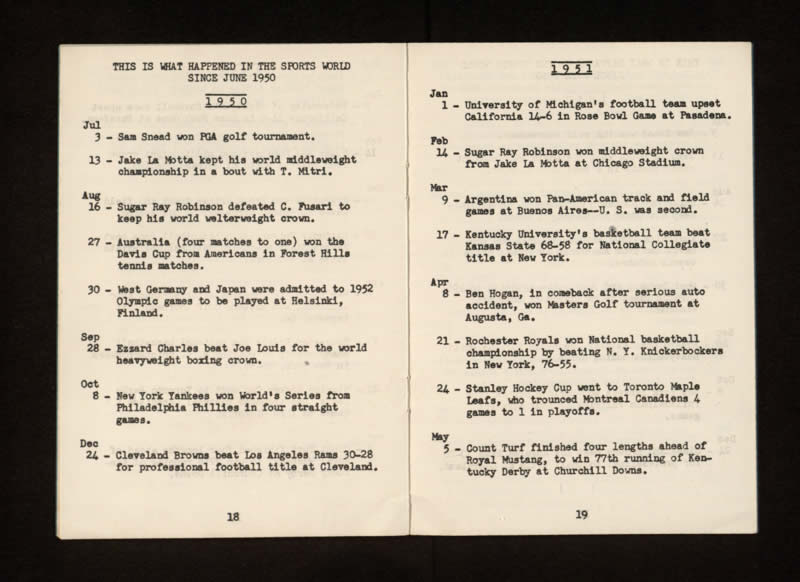

| Colonel Abbott and returning soldiers were apprised of major news events since their capture by this brochure. |

|

| Much of the news was tailored to the supposed interests of the American soldier: sports, entertainment, and politics. |

|

| A December 1953 Rochester Times Union article recounts Abbott's testimony about the horrific ordeal of his imprisonment. |